The sun sets around 4 pm at Haworth Parsonage in November. Charlotte Brontë intends to write a letter, but she must set up her writing desk near the window to make the most of the fading light. If she is sitting down to write, it is undoubtedly the time of the day allotted for the act of writing. Charlotte’s mother died when she was a little girl, and her family’s days were determined by her spinster aunt, her mother’s older sister who came to live with them and ordered their days according to a somewhat regimented schedule. Whether baking or washing or walking, everything was done at its scheduled time of the day.

Literacy reached its high-water mark during the 19th century. Books, newspapers, magazines, were the most common and consistent form of communication and the world of men and women was opening up more and more to what lay outside their immediate neighbors. The desire for information, for news about art, literature, government, religion, had long made up a significant part of Charlotte Brontë’s interests, who was devouring newspapers even as a young child. And the backbone of all this literary industry was the letter. Written in first person, detailing all of one’s personal concerns, the letter formed the basis of what is considered the first real novel, (Pamela, by Samuel Richardson, written in the 18th century). The epistolary novel, a story made of letters, was not uncommon, and most novels included actual letters between the characters, written word for word. The letter became a significant literary device among the Brontës, for Anne’s novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, is written in large part as a series of letters. Charlotte’s first novel, The Professor, begins with the narrator recounting his past experience to a friend in the form of letter. The act of recording one’s life in written words for one’s friends seemed to overflow into the business of creating fictional lives.

The other day, in looking over my papers, I found in my desk the following copy of a letter…

– The Professor, Charlotte Brontë

Few things are more significantly 19th century than letters. And for Charlotte, who had so few companions outside her own family that could penetrate her shy reserve, letters were her anchor and her prop.

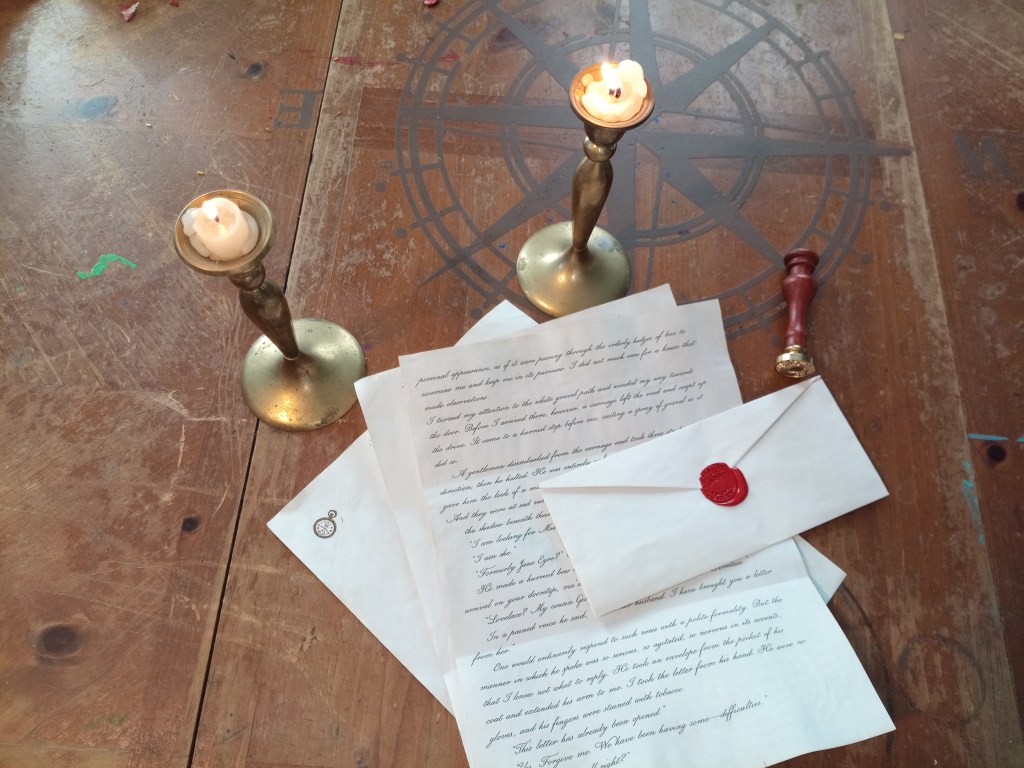

Brontë’s letters were written with bottled ink and possibly a quill pen, that would likely need sharpening with a penknife. She must take care not to cut her fingers in the process. If the ink grew too cold, it would not write as well. While letters had been the primary means of communication in England for some time, changes in the manufacture of paper made it considerably less expensive during Brontë’s adulthood than in her childhood. As a little girl, she and her brother Branwell had labored over tiny books made of odd paper scraps. These were cleverly designed to mimic the popular periodicals of the day, but were hard to read with anything but a magnifying glass. Now she could scribble away on a whole sheet with impunity.

But who would she write to?

Her most frequent correspondent was her friend Ellen Nussey. Ellen was her closest friend from school, who lived too far for regular visiting, but close enough for the occasional visit every year or two. Ellen was an unmarried woman, like Charlotte remained most of her life, and their friendship was very close. The personal, intimate quality of Brontë’s letters, her occasional confessions of sorrow, inadequacy, inferiority, or deep longing for the companionship of her friend, remind one of the close psychological portraits of her famous characters. Charlotte Brontë was long in the habit of detailing her own heart to her friend.

Her letters might all have been destroyed, if her husband’s request had been obeyed. After marrying Brontë, the love of his life, and now a famous author, Arthur Bell Nichols cautioned her about writing too freely to anyone. He was concerned about her public reputation, and perhaps rightly so, for rumors had been swirling about the mysterious Currer Bell (her initial pen name) for many years. By the time of her marriage, her real name was well known, but one never knew what sort of gossip might arise. Charlotte laughed at the thought that anything she wrote in a letter could be worthy of such notice, but she dutifully copied down Arthur’s request that her letters be burnt. Ellen, however, had never really like Arthur, and claimed she never agreed to such a proposal, and therefore kept the letters, to posterity’s relief.

While writing a novel at any time is no mean feat, Brontë’s novel writing had its challenges. The manuscript must be written by hand, frequently by candlelight, with ink that might stain her only clean dress. (Laundry was done by hand in those days and was back-breaking work. One did not wash their clothing unnecessarily.) Then it must be copied out, word after painstaking word, into a clean, final copy, tied with ribbon and sent in the mail, the precious package representing hours upon hours of work, only to be returned, declined by the publisher. Her first novel, The Professor, was sent out to one publisher after another for years before anyone took an interest. And even then, it was a publisher declining to publish it but requesting a look at any other work she had in hand. As it happened, she had already begun on a work about a rather unattractive governess.

She finished it as quicky as she could and sent it in, but not under her real name. She and her sisters preferred anonymity, and even her publishers did not know if she was man or woman, young or old, rich or poor. She kept up a regular correspondence with her publisher’s literary assistant, William Smith Williams, discussing by letter not only publishing issues, but their mutual philosophies on life. At one time it became expedient for Charlotte to go to London and introduce herself to her publishers in person, which she did without any warning. It was undoubtedly am unexpected meeting between this gray-haired London gentleman and this tiny parson’s daughter (Charlotte was only 4’10”) who had written so freely to one another of their serious thoughts on life.

When the letter is finished, it must be sealed with a wax seal. In her novel Villette, she describes the letter of a friend, and the personality of the character signified by his wax seal:

Graham’s hand is like himself, Lucy, and so is his seal—all clear, firm, and rounded—no slovenly splash of wax—a full, solid, steady drop—a distinct impress; no pointed turns harshly pricking the optic nerve, but a clean, mellow, pleasant manuscript, that soothes you as you read.

– Villette, Charlotte Brontë

In Villette she also gives the reader a portrait of the hardship of waiting for an expected letter, waiting days, or weeks in suspense, not knowing if the correspondent received your last letter, or is even at home, or likely to be back for three months or more. Communication in those days was unreliable and slow by our standards, to say the least, and the requisite patience needed when one was heartsore for a word of encouragement was a trial.

“A letter! The shape of a letter similar to that had haunted my brain in its very core for seven days past. I had dreamed of a letter last night. Strong magnetism drew me to that letter now; yet, whether I should have ventured to demand of Rosine so much as a glance at that white envelope, with the spot of red wax in the middle, I know not. No; I think I should have sneaked past in terror of a rebuff from Disappointment: my heart throbbed now as if I already heard the tramp of her approach.”

– Villette, Charlotte Brontë

Now that the wax has been melted and the stamp impressed, she must walk into the village to post her letter, and perhaps she will savor the walk, just as Jane Eyre does when she leaves Thornfield to walk to Hay in order to post Mrs. Fairfax’s letter:

The ground was hard, the air was still, my road was lonely; I walked fast till I got warm, and then I walked slowly to enjoy and analyse the species of pleasure brooding for me in the hour and situation. It was three o’clock; the church bell tolled as I passed under the belfry: the charm of the hour lay in its approaching dimness, in the low-gliding and pale-beaming sun. I was a mile from Thornfield, in a lane noted for wild roses in summer, for nuts and blackberries in autumn, and even now possessing a few coral treasures in hips and haws, but whose best winter delight lay in its utter solitude and leafless repose.

Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë

Note – Much of the biographical information above was taken from Charlotte Brontë, A Fiery Heart by Claire Harman

Leave a comment